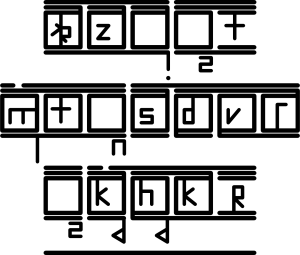

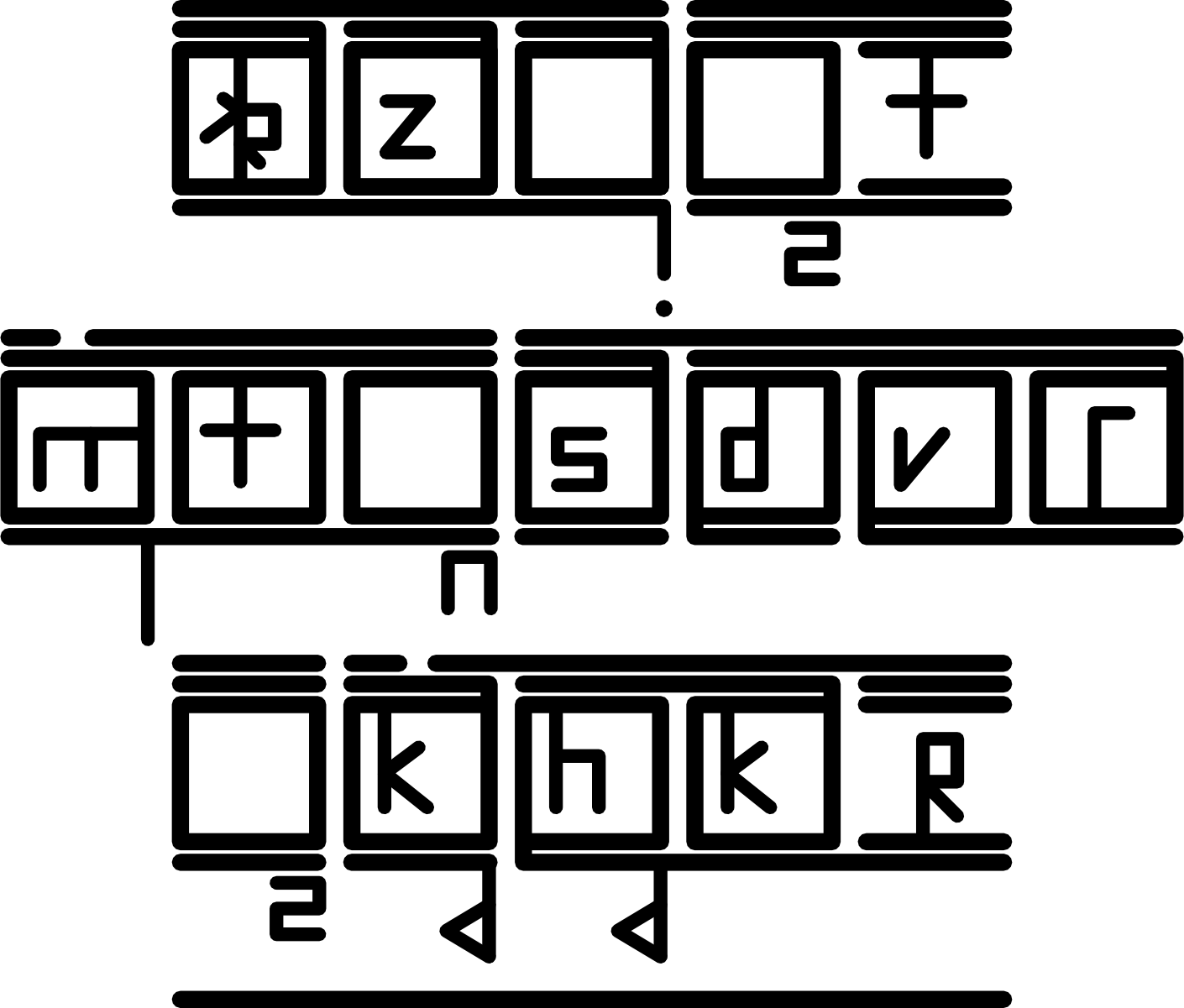

Or, I suppose, a new English script, depending on how you look at it. Way back at the beginning of this year, long-time Dothraki lajak Qvaak put together a new script for writing Dothraki. Those who’ve followed the blog a while will remember Qvaak also put together another script for Dothraki that’s based heavily on the romanization system. That one was pretty cool, but this one is quite a bit different. Take a look.

Pretty wild, huh? The above is the text from one of Qvaak’s haikus, which says:

Krazaaj osti

m’oltoon sadevesha

os k’athhethkari.

The script itself is actually derived from the roman alphabet (as should be clear with some of those characters, at least), but letters have been enlarged and shrunk and arranged into glyphs (and then into word blocks) in clever ways. Essentially the way it works is the glyph is based around the vowel of the syllable in question (that’s the big boxy part). The initial consonant is put in the middle and the coda consonant is placed on the lower right. The extra lines are either giving you information about word groupings or punctuation, or they’re there for decoration (to get rid of the blank space).

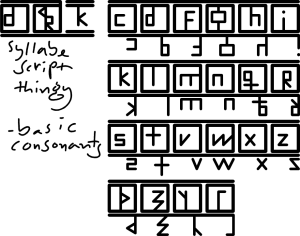

To get a handle on the system, here are all the consonants:

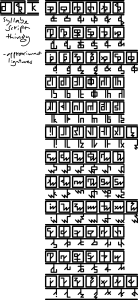

Here are some ligatures for syllable that start with a consonant and approximant:

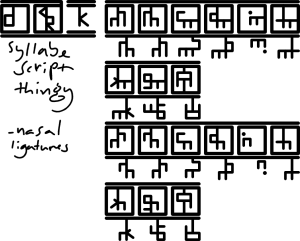

And these are nasal ligatures:

And now if you’d like a complete introduction to the system, this is Qvaak explaining exactly how it works:

Also, if you’re going to be in Southern California next week, I’m going to be doing a conlang workshop at WyrdCon. I’m also going to be on a panel with my colleagues from Syfy and Trion, Brian Alexander (writer for Defiance) and Trick Dempsey (creative lead for the Defiance game). Hope to see you there!

Wow! This is impressive!

Are you guys bored on the Roman alphabet that’s why you are creating a new ones? Kidding!

But ser… this is truly amazing!

Gosh I wish I had the determination to take these projects to the end. This curiosity is still decidedly unfinished and lost on the back-burner.

I love roman alphabet. That’s why I use (and modify) it instead of creating my own. And anyway, I’m happy having illiterate Dothraki, so we don’t need any canonical or semicanonical writing system, IMHO. And I would probably not have energy to learn to read any completely new system anyway, so these kind of exploerations are more fruitful.

The way different kind of writing systems highlight different aspects of language is interesting, so it’s fun to experiment.

For me it was complete enough to put up and I really like it! Though I do like the ones that looks less like roman letters more than the others. It’s a neat look.

Yeah, I agree with this.

Beautiful. Just Beautiful. I wish there was a way we could learn how to actually write it like how to construct words and such. I think it would be a cool kick to send a letter to the Nieces in Dothraki. They are major game of thrones fans, I’m only starting the book and television series.

I rather like this script. It is rather unusual, and about as far from what I would expect a Dothraki script to look like. But because it isn’t what you would expect, that makes it plausible!

Can’t say the aesthetics work for me… very technical, and most of the ink appears to be invested in scaffolding that doesn’t contribute to the information content.

It’s certainly original, though!

By the way, I’ve been contacted by someone who wanted a Dothraki phrase written in Tengwar for a tattoo… Culture clash aside, how would you do it?

I’d probably go for CV syllable, since then you can immediately see the stressed syllable — the first tengwa from the right without a tehta closes it. Perhaps use the double-stemmed voiceless velar glyph for Q?

I don’t know anything about Tengwar, so…beats me! Why not just use the “q” letter for [q]? That’s what we do in English, anyway.

Quenya mode has a labialized velar series including a /kw/ that is transcribed as {qu}, whereas Sindarin mode (and the General Use mode canonically employed for English) uses that series for regular velars, and Quenya’s velar series for palatals. Dothraki requires a palatal/postalveolar series, so it should be based on the Sindarin/General mode, which has no “q”.

I guess the double-stemmed velar tengwa would be the best match.

Well… certainly if you were to use tengwar there probably the Black Speech mode would be useful, considering the use of sh, gh, you could definitely use a long-stemmed k for q as a special symbol. Also this mode doesn’t have ‘o’ (or e for that matter, but they are somewhat compatible).

When you construct a paradigm of a writing system, a rather clean, computer-age look is usually the most natural starting point. I’m sure you might easily create fonts that would have a primitive feel in them.

I actually think a writing system like this implies primitive culture. The symbols are geometrical and text must be more constructed than written, but there is certain level of illogicality. To me that hints on the writing system only used by few and on some narrow purpose like weaving or chiseling charms on items.

If you had people writing shopping lists, I bet the system would soon deteriorate to some more flowing, less geometrically constrained paradigm.

You’re right, this does make a lot of sense in weaving. Kinda like Nüshu

Over on the Game of Thrones Wiki, we attempted to cobble together a linguistic map of Westeros and Essos: http://gameofthrones.wikia.com/wiki/File:Language_map.png

Well, I started one but I can’t draw well on a computer so Werthead made a better version which we’re now using. Not shown are the Summer Islands and Asshai, because HBO hasn’t given their location on a map yet (the Season 2 opening credits for Qarth do not match the revised maps from Lands of Ice and Fire, because they weren’t released yet).

Anyway, as you can see no attempt was made to show the subdivisions of “Low Valyrian” – particularly because it would look weird on a large global-scale map like this – maybe a future zoomed-in map of just the Free Cities might attempt that. But it didn’t fit this scale too well so I just made a swath of red from Braavos to Astapor called “Valyrian languages (all variants)”.

Werthead’s revision updated this slightly, because he felt “Ghiscari Valyrian” was distinct enough to warrant a separate color, orange.

This in turn led to a larger debate over the status of “Old Ghiscari” as mentioned in the Season 3 finale: is “Old Ghiscari”, the language of the Old Ghiscari Empire which was defeated by Valyrian 5,000 years ago, a “dead language”?

At first, my understanding from the books was that it largely died out, and its greatest influence on the modern day was that it influenced the variants of Valyrian spoken in Slaver’s Bay — just as “Gothic” or “Frankish” merged over time with Vulgar Latin to become Old French, and you can point to certain words in French today and say “this word is of Frankish origin” or even “this rare word is of Gaulic origin”, it is still a “French” word, not a Frankish Germanic one.

Thus my impression was that the inhabitants of Slaver’s Bay basically speak a variant of Valyrian, peppered with isolated words here and there from Ghiscari, i.e. basic words such as “mother” (Mhysa).

At first, the books pretty much say they speak Low Valyrian (and the wealthier slave masters speak High Valyrian):

But then in a later scene, its mentioned that Slaver’s Bay is actually a very polyglot society, given that slaves are brought in from all around the world. Particularly, when the freed slaves hail Daenerys as “mother” in the books they do it in no less than five languages: Mhysa, Maela, Aelalla, Qathei, and Tato are given as names for “mother” – each is “mother” in a separate language, but only “Mhysa” is identified (its from Old Ghiscari).

So putting all differences aside on how best to categorize the Valyrian variants heard in Slaver’s Bay….are other living languages spoken in great number in the area? I mean presumably quite a few Sothoryos langauges might be heard – slaves like Missandei coming in, but I don’t know if the slaves have enough freedom of movement to maintain their own languages amongst themselves.

But the big question is about Old Ghiscari: is it a dead language? If it is, how can they be shouting “mhysa”? It it just a word that survived into Slaver’s Bay Valyrian which originated in Old Ghiscari?

For that matter, speaking High Valyrian is seen as a status symbol in the Free Cities, a sign of refinement – would the wealthy slavemasters of Slaver’s Bay also pride themselves on speaking High Valyrian, as the Latin-analogue which is the language of all educated/refined people?

Or, conversely, would the current slave-masters in Astapor, Yunkai, and Meereen place greater value on intentionally reviving Old Ghiscari to assert their cultural independence from their old Valyrian overlords?

Thus, would surviving “Old Ghiscari” (if any survives) be found at the lower levels of society, kept alive away from the Valyrian overlords, or conversely, is “Old Ghiscari” something only the power elites of Meereen are trying to revive?

I’m deeply confused about the linguistic makeup of Slaver’s Bay.

And that’s not even getting into talking about sub-variants of Valyrian.

I guess Astapor, despite being polyglot to some extent, can be comfortably marked as “Ghiscari Valyrian”-speaking, as this would be the majority lingua franca.

In the same way, New York and other large US cities can realistically be marked as being in an “English” zone on a linguistic map, despite enormous immigrant communities where e.g. Spanish or Cantonese might predominate in certain neighbourhoods.

Not sure about the rest of the world, but in pre-modern Europe, a great deal of cities were heavily polyglot, even if the surrounding peasant society was essentially monoglot. One characteristic you see a lot in German-speaking areas is that the dialect of the working class of a particular city can be markedly different from the dialect continuum that surrounds it. Berlin and Vienna definitely fit this – as the capitals of their respective kingdoms/empires they became melting pots and their distinctive “city dialects” (although declining in use) to this day remain quite different to the surrounding areas.

Since it’s a trading port, probably. People come from all over not just as slaves, but as traders, too. Those wishing to sell their goods (or people) will need to be communicate with as many buyers as possible.

Yes.

This is event is so common as to be completely unremarkable. Old English is a dead language, for example, but we’ve got plenty of words that were in use them in English. Latin, too. A single, common word? It survives because people remember it and keep using it. You can take a noun from any language and use it another. Think, for example, what would happen if every Japanese-speaking person switched to some other language over night and forgot Japanese. In English, we’d still have the words kimono, sushi, etc. They’re not likely to go away just because the language they came from died.

This seems likely.

This seems less likely.

I don’t see the language as having survived in any form. George R. R. Martin specifically describes a creolization situation after the Valyrians sacked Old Ghis for the fifth and final time. I, though, would imagine that even that basilectal form de-creolized a bit and became more like other Low Valyrian languages. But, of course, in all creoles plenty of non-lexifier vocabulary is retained.

I have adjusted the language map and “Old Ghiscari” page to take into account that it is in fact a dead language, thank you.

A separate question has arisen regarding the Dothraki, and I’m sorry if this may have been asked before:

In “The Night Lands” Rakharo’s decapitated head is sent back to Daenerys, and Irri weeps that they’ve practically killed his soul – they cut him up like an animal. So over on the “Great Stallion” article on GoT Wiki, I took into account Drogo’s earlier threat that he would not honor his enemy by burning his corpse by leave him to rot, and said that:

But just now I ran across that, in the books, the Dothraki have special riders that go around the battlefield after the fighting is over, called the “Jaqqa rhan” (Mercy Men) who are explicitly charged with “taking the heads” of the dead or dying.

How do we reconcile the Jaqqa rhan with TV-Irri’s claim that decapitating Rakharo was practically killing his soul?

I’m confused: do the Jaqqa rhan take the heads of *Dothraki* dead, or of people they air raiding? (i.e. Lhazareen). If decapitation is seen as such a grave desecration, wouldn’t it be odd that the Jaqqa rhan exist for the dedicated role of decapitating fallen enemies, when one Dothraki khalasar fights another? Wouldn’t this be utterly insulting to do to other Dothraki khalasars?

I understand that part of the situation is that Rakharo *didn’t* get decapitated in the books, and Irri’s lines only exist in the TV series.

As I said in the quoted block text above, I incorporated this as “dismembering the body as one would an animal and then leaving the pieces to rot” is what is bad; but that somehow a distinction exists between this and when the jaqqa rhan, perhaps solemnly, decapitate the dead or dying *in preparation* for burning the head and body on funeral pyres after the battle is over.

In short: how to reconcile TV-Irri’s lines about Rakharo’s decapitation with the jaqqa rhan of the books?

In other news: the cowards on Wikipedia.org have deleted the page on “Species in Defiance” which I wrote throughout Season 1. The bastards. But I did have a lingering question: the name of the Castithan/Indogene homeworld is “Daribo”, right?

Well I was leafing through my Asimov “Foundation” books and I recalled the names of the original “Four Kingdoms” which surrounded Terminus (the first four barbarian kingdoms in their immediate vicinity after the the Galactic Empire starts breaking up). The one we hear about almost entirely is the most powerful planet, Anacreon.

However I was thumbing through, concerned I forgot all four, and discovered that they are: Anacreon, Smyrno, Konom, and “Daribow”.

So is the name of the Castithan/Indogene homeworld a shout-out to Asimov? A tip-of-the-hat to another space opera? Or is this simply a massive coincidence that “Daribo” is so similar to Asimov’s “Daribow”?

I don’t see anything that needs to be reconciled. All of the facts you mentioned seem to sit perfectly well together, as I see it. Where there may be confusion is the jaqqa rhan who, as far as I know, ride through the enemy lines and kill those yet alive, not their own lines.

To me it seems like a not-very-massive coincidence. It’s a three syllable word made up of open syllables, all of which can occur in English. One is bound to come up with two that sound the same (unless, of course, Asimov meant it the last syllable to have the same vowel as in “cow”, in which case they’re not identical in sound). But, no, I never read that. Daribo was one of several names I suggested for the Castithan/Indogene home world, and it’s the one they liked the best.

Continuing from IRC…

By our wiki’s current knowledge, this should be all consonant clusters that should fit on the onset of a syllable (and of course, reversed in the coda):

kr gr dr tr qr chr jr vr fr khr zhr zr shr sr thr mr nr hr rh

kl gl dl tl ql chl jl vl fl khl zhl zl shl sl thl ml nl hl lh

kw gw dw tw qw chw jw vw fw khw zhw zw shw sw thw mw nw hw wh

ky gy dy ty qy chy jy vy fy khy zhy zy shy sy thy my ny hy yh

km gm dm tm qm hm mh

kn gn dn tn qn hn hn

kth gth qth

ks gs ds ts qs

ksh gsh dsh tsh qsh

kz gz dz tz qz

kzh gzh dzh tzh qzh

gkh dkh tkh qkh

kf gf df tf qf

kv gv dv tv qv

well, actually affricates are grouped with stops, so according to the current explanation, stuff like jkh or jm should also work. But as affricates are pretty much fricatives with an attack, they would result in two fricative sounds in the same onset (or fricative sound followed by nasal), and that does not seem right

I’m also a bit unsure, what clusters are eliminated by stop + fricative on the same region results in geminate fricative rule, but I hope I’ve got those right. Would that work for affricate + fricative too?

Anyway, that is more or less the set I tries to make ligatures for, since I figured most would appear, if not elsewise, at least on compound words. But I began to seriously doubt my set along the project. Some further clarification on what fits to onset, what is assimilated into something else and what can just never happen (w at least might just have too retricted environment) would be nice. It’s been some time since we’ve learned anything more than new words from Dothraki.

As for what we’ve actually met in action, as word starters we have dr, fr, gl, gt, gw (interjection might not follow phonotactics but we also have a few mid-word gw for a support), hl, hr, kr, mh, mr, nh, nr, ql, qw, rh and vr. There are of course some more from word endings (ast gives us ts), three consonant clusters and what have you (zhokakkwa gives us kw), but I’ll have to take more time if I’m to dig them all out. It’s unusual enough to find even two consonants one after another, so most combinations on the list have never been seen at all.

There’s a lot that isn’t right here… For example, you can’t really ever have a mismatch in voicing even across a syllable boundary, so you’d never see [g.s], [d.s], etc., but certainly never as the onset of a syllable. That would be completely impossible. In general, you can’t have a stop followed by a fricative as an onset (the only counterexamples being the affricate phonemes, which are a special case). You also can’t have anything followed by a nasal being the onset of a syllable. Basically, all these are out:

There’s also a sound change that probably isn’t very well advertised because I can’t imagine when it would be important for the user (only in compounds, maybe?), and that sound change is this:

/r/ > [l] / /q/_

So you’ll never have /qr/ in Dothraki. Those sequences are always realized as [ql]. There are also no sequences of “chy”, “jy”, “shy” or “zhy” for historical reasons. Also /lh/ is out. Otherwise, that should be good…

Interesting!

The restiriction on voicing mismatch I sort of guessed myself after I sent the post. There’s been some talk about that. I’m guessing the preceding sound dictates the voicedness of the following one?

You included hm, mh, hn and nh to the no-list (not nh tecnically, since I typoed it into another hn)… I’m guessing you just missed them. Mh and nh are in use. Hm and hn should be impossible, if nothing can precede nasals on onset.

I thought onsets and codas worked symmetrically, but now it seems this is not the case. Ts is not acceptable onset, but st is an used coda. Are there many clusters without mirror vesions allowed?

At least shy and zhy seem like sequences that should happen now and then at least on compoundword boundary. What happens then? Is the fricative just left on the coda or does something change?

I did miss mh and nh. But neither hm nor hn would be acceptable onsets.

No, this isn’t the case. Consider English, for example. We allow both [ts] and [st] in coda position, but only [st] in onset position.

If it was a common compound, the y would drop out (maybe producing a geminate). If not, I think they would stay in separate syllables.

We have the set of possible onsets down at

kr gr dr tr chr jr vr fr khr zhr zr shr sr thr mr nr hr

kl gl dl tl ql chl jl vl fl khl zhl zl shl sl thl ml nl hl

kw gw dw tw qw chw jw vw fw khw zhw zw shw sw thw mw nw hw

ky gy dy ty qy vy fy khy zy sy thy my ny hy

rh wh yh mh nh

…which seems pretty nice small set. Approximants preceded by stuff plus the special case of h. I still have a bit of trouble with vw and perhaps some other w stuff, but it’s probably me. My w isn’t terribly strong.

Now if we just manage to get the allowed coda combinations, I might even properly finish my glyph set.

There’s nothing surprising, per se, in the fact that coda set is different. You just said originally that the rules for onset mirror for rules in coda, which, I guess, is true for the general rule-of-thumb approach we had.

With codas, though, there does not seem to be any “all sequences are possible and must be resolved in some way at least on compound word border” type of reasoning. It seems big codas are usually a result of the dropping of word’s final vowel due to declination, but this means the consonant sequence must already be available in the word.

David, if this is what you can do for a bunch of illiterate savages like the Dothraki, I’m looking forward to seeing what kind of script you come up with for High/Bastard Valyrian.

Question: was it ever, retroactively, worked out what the names of the dragons mean in High Valyrian? Balerion, Meraxes, and Vhagar were named for gods of the old Valyrian pantheon. I don’t know if these word-elements were decided to have meaning to them.

Moreover, we have some new dragon names from the Dance of Dragons:

Syrax

Caraxes

Tessarion

Meleys

Morghul

Shrykos

Vermax

Arrax

Tyraxes

Could these have identifiable HV word elements?

If not, will new word elements be gleaned from them?

Later generations of the dragons often stopped using HV names and instead descriptors like “Silverwing”, “Moondancer”, etc. There were even a few “wild” dragons in the Dance, who hadn’t been tamed as hatchlings due to no dragonriders being available. They grew up wild on Dragonstone and just had basic nicknames applied to them by the commonfolks whose livestock they raided. Ironically, this meant that one of the major dragons in the Dance was named simply “Sheepstealer”.

I always incorporate the dragon names (i.e. make sure they have a declension pattern, etc.), though sometimes with minimal changes (for example, there’s no [ʃ] in High Valyrian, but there is in many of its daughter languages, and that pronunciation often is used in modern High Valyrian words—like pronouncing Cicero with two [s] sounds when speaking Latin). I haven’t done meanings for most of them—and the same goes for people’s names. I want to hold off until we learn more from GRRM.

Where are you getting those names from? Please tell me the reference.

GRRM has been doing live reads of “The Princess and the Queen” at conventions, and roving reporters posted their copious notes to Westeros.org.

I, in turn, wrote up a “narratized” version which collected these reports into a single coherent narrative:

http://gameofthrones.wikia.com/wiki/User_blog:The_Dragon_Demands/The_History_of_House_Targaryen._Part_IV:_The_Dance_of_the_Dragons

Caraxes is my favorite, followed by the rags-to-riches story of Sheepstealer. Vermithor was really a dick, though.

Shockingly, it turns out that *the Dornish actually managed to kill Meraxes*. I mean previously GRRM has publicly said that “Meraxes died in Dorne” but we never knew what that meant exactly. Turns out that they took down Meraxes with sustained crossbow fire, eventually piercing its eye into its brain. It isn’t for naught that House Toland’s sigil is a dragon running in circles around its own tail. They have mentioned off-hand in the books that “sustained arrow fire can potentially kill a dragon” – it’s why Aegon I was nervous about committing all three dragons to the Field of Fire. Meraxes proved this.

Otherwise, apparently both Meraxes and Vhagar laid eggs which hatched into other dragons: they get referred to as “she”, as do other dragons like Syrax, Meleys, and Tessarion – even by a maester who allegedly didn’t believe that they could change gender; thus he’d only call them female if it was known they produced eggs.

Wow! Haven’t read that! Thanks for it.

Thanks for all the information btw.

Morghul is clearly intended to mean “death,” but in DJPian High Valyrian “death” is morghon, whereas the -ūl- in morghūlis seems to be a verb-forming suffix (cf. rāpūljagon “to soften,” and *obūljagon “surrender”—not attested so far, but I’m guessing it from the noun obūljarion.) I suspect āeksio Peterson will have to treat this as a borrowing from a Low Valyrian language (or the like), as he did with Rhaegal, but it will be cool if there’s a way out of that.

Okay, turns out we have bigger problems: Jacaerys I’s dragon was named “Vermithor” (I missed him in the above list), and Rhaenyra’s son Jacaerys “Jace” Velaryon’s dragon was named “Vermax”. Clearly then, the stem “Verm-” must mean something in the old Valyrian pantheon.

Out-of-universe, the problem is that in episode 4 of Season 1 (“Cripples, Bastards and Broken Things), Viserys lists off some allegedly Targaryen dragons…possibly just made up on the spot. They don’t correspond to the Targaryen dragons listed in the Princess and the Queen (there were only under two dozen of them). We can get around this by saying that he was just listing off *Valyrian* dragons from before the doom (or, that it’s been so long that Viserys doesn’t remember the names correctly! He doesn’t even know what dragons look like! The dragon sigil on his chest portrays them with four legs in addition to two wings…he doesn’t know anything about anything).

At any rate, one of the dragons Viserys listed off in that episode was “Vermithrax”….which is actually a reference to the 1981 fantasy film “Dragonslayer” — one of GRRM’s personal favorites. The dragon in that movie is named “Vermithrax Pejorative”….GRRM said it was his favorite movie dragon of all time (Reign of Fire’s dragons being a close second).

So apparently, I don’t know if the copyright boys got upset that they used “Vermithrax” in Season 1 of the TV show, but in the books, I suspect that “Vermithor” and “Vermax” are themselves a shoutout to Vermithrax.

The linguistic complication of course is that “Verm” stems from the old Germanic for “Worm” – a dragon is a serpent/snake, a long-worm (Tolkien uses this more). I forget which germanic language “verm” stems from.

Point is that the stem clearly has some High Valyrian meaning but has an out of universe origin.

I don’t see any language problems here at all—though you do bring up an interesting legal point re: Vermithrax. I guess you can probably say whatever names you want, though, if it’s done in the context of a reference, without having to pay anyone royalties.

It could also just be a difference in continuity between the show and the books. It’s not like there haven’t been plenty of those already, especially in the details of the Targaryen line.

Oh, and I assume Vermithrax is more directly representative of Latin vermis, which is often conflated with wyrm.

Ah, turns out it’s a shared Proto-Indo-European cognate. http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/vermis

I always had the pet theory that the name should be retconned to ‘Vermithorax’ as in “Worm-chest” or “Worm-cuirass”. It could be in reference to the supposedly weak dragon underbelly (though of course this is not the case with Martin’s dragons in the story, but acknowledge as a popular belief). In any case I think it makes much more sense than “Worm-Thracian” :S

For all we know, of course, younger Dragons from the Dance era (150 years ago) could simply have used Low Valyrian names because all of the High Valyrian names from gods of the Valyrian pantheon had been exhausted.

Yeah, actually that was my pet theory: Morghul is a Low Valyrian (or even just Westerosi Common) form of something like, say, *Morghūlion.

One of the problems I’ve run into, in my actual “professional” work on my thesis, is that the shift from “Classical Latin” to “Romance Languages” was not like flipping a switch, but an evolution.

Very broadly, Classical Latin turned into “Medieval Latin” (call it Ecclesiastical depending on your preference I guess). Even this ignores the “Church Fathers” era as a distinct unit but that was sort of blurred. I’m comparing “the language of Cicero, Virgil, and Marcus Aurelius” with medieval charters from c.1200.

But this was already starting to turn into Old French. So one term I looked up, “Vavassor”, I had to ask a department professor who is a big vernacular expert, and even she said that “Vavassor” was a term from both Medieval Latin and Old French – it starts to appear after the Classical period.

The Fall of Rome/Doom of Valyria are convenient cutoff points, but we need to work out how the dozen or so Low Valyrian dialects branched off from each other (pet theory was always that those along the Rhoyne would be similar due to Rhoynish influence, but we don’t know much else about Essos’s history).

My point is…like, when the writers just made up a word for “yeah” that Talisa says when she’s writing a letter, we just had to assume it was “Volantene” or something.

BUT, we might be able to get away with saying “there’s even an “Old Volantene” which was a transitional stage between High Valyrian and Volantene Low Valyrian — thus any unusual names from the books which don’t fit the pattern might just be “a surviving Old Volantene archaism”.

Agreed on all counts, though to continue the analogy, it seems to me much easier to imagine a Medieval European dragon named, in Latin, “Murdrator” than, say “Necus” (But then, you never know with Medieval Latin, and I could certainly imagine Necus in a fantasy novel )

)

Er, in case I’m not clear there, my meaning is: it’s a lot easier to imagine a non-classical word of foreign origin with a classical suffix, than a name from a classical root with a badly formed ending. So really I should have had the dragon be named “Nec” or “Interfic” or something like that… hard to imagine either of those being Latin names, even though they’re both perfectly good Latin roots.

In the orthographic transcriptions of words such as “arakh” and “khal”, the plural forms take on an “s” at the end of the word. In the phonetic transcription, would the “s” be realized as a “z” after voiced consonants such as it is with English plural forms?

Are you talking about the English words “arakh” and “khal” borrowed from Dothraki? You could do whatever you want. I’d probably use the phonetically-appropriate forms, but Qvaak invented the system, so he might have an opinion. I don’t know if he envisioned using it for writing English, though.

What I mean is in the books the plural form of the Dothraki words have just an additional -s at the end of the word.

ex. “They held their arakhs.”

Is this how plurals are actually formed in the language?

If so, in words that end in a voiced consonant, such as “khal,” would the plural -s be pronounced as a true voiceless “s” or would it assimilate to the voiced “l” by being pronounced as a “z”?

Otherwise how are plurals marked in Dothraki?

See this article and this article from the Dothraki wiki. How (or if) a noun is pluralized depends on its animacy and the role the noun plays in the sentence.

The reason the plurals in the book take “-s” is because the words are being used as English nouns. For example, the plural of “kimono” is “kimonos” in English, but not in Japanese. It doesn’t matter what the plural is in Japanese, though, if you’re using the word “kimono” in English, and the same generally goes for any borrowing. For certain languages we’ve borrowed in plurals (for example, many Greek and Latin words have a special plural we’ve borrowed in—and Italian too, for some reason, even though we don’t with French and Spanish), but for the most part, all borrowed words are treated as basic English nouns.

So, for example, if one were to say, “I have three arakhs” in English, you’d say it just like that, because “arakh” is being used as an English word. In Dothraki, though, you’d say, Sen arakh mra qora. In this case, the noun bears no marking for plural or singular, since it’s inanimate.

I don’t think “khals” and “arakhs” are intended to represent Dothraki plurals any more than say “ninjas and shoguns” says anything about Japanese, or “Caesars and spathas” about Latin.